Man helped double-check sums keeping Apollo 11 safe

The Apollo stories: Dennis Sager was one of the last employees of the human-led backstop for the computation that made the mission possible.

by Erin Winick April 3, 2019

In the months leading up to the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, we will be sharing the stories of the people who made the moon landing possible as part of our Airlock space newsletter. (Check out our last story, “The man behind the Apollo boot print.”) This week: Dennis Sager.

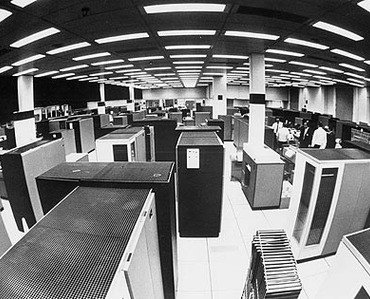

In space, your calculations have to be right. That means you probably want someone to check your work. The bulk of the computation for the Apollo missions was carried out by the Real-Time Computer Complex (RTCC), a room of computers developed by IBM. But relying entirely on one set of machines for such a critical series of missions was not enough for NASA.

So the agency also employed a whole backroom of expert mathematicians who used some good old-fashioned punch cards to double-check the main machines’ computations. The facility operated during the Gemini and early Apollo missions. Dennis Sager was one of the youngest in that backroom of Building 30 in Houston, Texas, also known as the Real-Time Auxiliary Computing Facility (RTACF).

As well as marking the machines’ homework, the group’s job was to help the missions prepare for the unexpected—and adapt when circumstances changed. While the RTCC had to lock in its code and trajectories before launch, the RTACF was agile. “We were able to make changes on a real-time basis on the flight,” says Sager. “We could do things that weren’t even thought of beforehand.”

His room was tasked with things like figuring out how to guide the mission if a hurricane hit the Gulf of Mexico, and calculating trajectories several orbits ahead of the spacecraft’s current position in case of an abort or error.

That meant they were thrown quite a few curveballs. One came in the form of a surprise Russian spacecraft. During the Apollo 11 mission, the Americans weren’t the only nation headed toward the moon. The Russians had launched an uncrewed satellite, Luna 15, that was designed to snatch away a US first.

“They intended it to land on the moon, grab some rocks, fire some of the rocks back to Earth, and say they got the first rocks back and beat the US,” says Sager. “They were going to get back a day or two ahead of the Apollo 11 mission.”

But although it’s been reported the Russians released the flight plans for Luna 15, Sager says his team at the RTACF never got the orbit info on the craft. “[We] calculated the orbit to make sure it wouldn’t be anywhere near where Apollo 11 was,” he says. They were able to do this by using observations of the craft from data provided by a British observatory. In the end, Luna 15 crashed into the moon a safe distance away, just a few hours before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin began their journey home.

After Apollo 11, though, things changed. Technology was improving. The main computers were more adaptable and no longer need a redundant checking system. Basically, the RTACF wasn’t necessary anymore. So for Apollo 12, there was some major downsizing.

The staff of the RTACF was reduced to two people: Al DiValerio and Sager. According to Sager, DiValerio was the nice “old man” of the RTACF. He was 34 (feel old now?). But sadly, he died of a heart attack at home during the Apollo 12 mission. That left Sager as the lone remaining employee, and while others helped him out for the mission, he knew it was time to move on. “I gave notice that I was leaving after Apollo 12 on the Apollo 12 launch morning,” says Sager.

Soon after, he left aerospace to pursue a career in medicine. “There was sort of a post-Apollo letdown across the country,” says Sager. “A number of us left engineering and went to medical school. So I went and became a doctor.”

Sager never lost his desire to work in space. Years later, he actually applied to be an astronaut. He got the call to come to astronaut interviews, but his poor eyesight snatched that opportunity away. But, like so many other Apollo veterans I’ve talked to, he said he was glad to have been involved when he was. “Working on Apollo was just unbelievable,” he says. “It isn’t like I discovered anything personally. They would have gone to the moon without me, but I was lucky I got to work on the mission.”

Sager now lives in Virginia. He works as a primary care doctor and performs FAA medical exams on private and airline pilots.

This article first appeared at MIT Technology Review on April 3, 2019.

No Comments